I was sitting at the top of the stairs leading down to the lake when she approached quietly from behind. She asked if I could move, as she usually leaves her mobility trolley there before swimming. I stepped aside so she could park it against the rails. “Sorry, I’m such a cripple,” she said.

It happened to me in Hungary this summer, a country where ageing has been seen quite one-dimensionally.

In my home country, getting old feels like a dark pit you can’t avoid.

Descending into a time of low pension, incurable pain and diseases, crooked backs and short, permed hair. You’re invisible, you’re a burden, and the Western, upper middle-class notion of a peaceful retirement somewhere beautiful (or even a fairly comfortable life after leaving the working world)feels like a cruel joke.

Among my friends, the most common stereotypes about old people are that they are either sweet grandparents nagging you to eat more, vicious hags terrorising youth on public transport in their eternal hunt for seats, or brainwashed believers of the right-wing government with a photo of Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary, on their nightstands.

They are not thought of as women who go for a casual swim in the same lake as I enjoy taking a dip in.

Getting Old? In This Economy?

Three years ago, when I moved to the Netherlands, was the first time I saw old people sitting in cafés with a straight back, having fun or doing sports. I was genuinely shocked when a man, looking 70, jogged past me while I was walking my dog.

We could easily attribute these differences to the economic disparities between Hungary and the Netherlands, but the lack of money isn’t the only thing that can spoil the experience of getting old.

Hungary isn’t alone in treating older people as a “social problem”. As Frida Kerner Furman notes, “our society is age-segregated”, referring to our late-capitalist, individualistic Western culture. In the Western world, where value is tied to productivity and purchasing power, and where social media has inflated the importance of looking desirable, ageing often means losing relevance. This is especially true for women, who are historically more vulnerable financially and whose value is often conflated with their appearance. For those who identify as women, ageing translates to a loss of perceived beauty (which is, in our primal brain, associated with fertility – whether or not we have a functioning womb), therefore femininity.

From puberty on, women are taught to mask their age.

Shaving off your body hair as soon as it appears, dying your hair at the sight of the first grey strands, or a 9 step skincare routine to defy the laws of physics and the effects of biology. Many natural aspects of womanhood, such as, hair, cellulite or even periods, are simply deemed disgusting. Several feminist writers claim “the infantilisation of femininity” is alive and well, i.e. the societal effort to keep women vulnerable and weak, or as de Beauvoir wrote to keep them in the state of “the eternal child”.

However, you can only fake youth for so long. An (ironically) very much ignored and understudied phenomenon, the “invisible woman syndrome”, hits women around their 40s. With menopause, the loss of youthful appearance and the slow decrease of purchasing power, women enter a state of irrelevance, feeling almost unseen, an issue addressed by more and more writers of the “invisible” age.

On Ageing “Gracefully”

This segregation and the shameful invisibility are challenged by the fierce and unapologetic group of “granfluencers” whose mission is to show that old people don’t have to live a boring and miserable life, and getting old doesn’t necessarily mean getting “ugly”. “Granfluencers” are cute, empowering, entertaining and inspirational. Look at that old lady, enjoying life, wearing bikinis, preaching feminist ideas, giving advice on how to build your own independent life without men, because who needs them?! They also offer us a peek at a highly romanticised, consumption-oriented, very gendered, many times overly sexualised, incredibly Eurocentric (especially Western European), white and classist lifestyle, unattainable to literally 99% of womankind, let them be cis or trans, gay or straight.

If anything, they might even add more pressure and anxiety to this new buzz around “ageing gracefully”. A term that should or could mean people accepting and embracing their unique ways of ageing, slowing down, changing, growing into something more wholesome, accepting the process of the passing time.

However, as Dr Stephen Bresnick, a Californian plastic surgeon explains in his blog, this understanding of the phrase is “negative” and limiting, because it urges real acceptance. He’s quick to reassure it doesn’t mean “you have to wear your wrinkles with pride”.

Ageing doesn’t have to mean irrelevance. “If you feel energetic and youthful internally, then there’s no shame in getting a facelift, tummy tuck or breast lift to keep your body at the same level,” he writes. Almost as if he suggests that getting old is fine, as long as you do everything to deny your body the natural ageing process. Don’t be ashamed of feeling ashamed, just throw a little money at it.

Rethinking Ageing

“Feminist thinking is really rethinking”, says Myra Jehlen, a feminist scholar. Therefore understanding that there’s much more to women than their appearance. And with getting older, looks aren’t the only thing that change.

Rethinking ageing involves recognising its intersectionality and acknowledging that the issues discussed here are shaped by Europe’s individualistic culture.

Collectivist societies or tribal cultures might have a perfectly different perspective for the elderly.

The notions of las curanderas in South America, or aunties in India whose opinions can heavily weigh on the future of young people when it comes to choosing a partner or a career, demonstrating that older women can have agency in ways we might not expect.

Exploring diverse representations of older women not only helps us choose our own path but also allows us to create a range of new possibilities for ourselves without having to comply with unrealistic beauty standards.

The Dangerous Old Woman

In “Women Who Run with the Wolves,” Clarissa Pinkola Estés explores how patriarchal strategies, illustrated through South American and Slavic folklore, alienate women from their true nature (and nature in general). She argues that this is done to keep women under control, as their authentic power would threaten the status quo.

Amanda Barusch, a researcher specialising in gerontology, is particularly interested in “older women who resist invisibility, who reject the conventional shape of old age and redefine later life”. She calls them “mavericks”, and one of their subtypes is “the crones”. The word “crone”, according to the Oxford dictionary, describes “an ugly old woman”, and by taking back such a negative phrase, it’s also meant to include women from any race, class and religion. Crones reject society’s “anti-ageing pressure”; they embrace the wisdom of later life and getting old on their own terms. They also strive to create communities where women can support each other.

“There are things the Old Woman can do, say, and think that the Woman cannot,” Ursula Le Guin writes in “Space Crones”. But what might an old woman say if we asked? She might tell us that spending hundreds of Euros to look “good” isn’t worth it, that we should embrace laziness and freedom over humility and modesty, and that dying “alone” is, ontologically, inevitable—but it’s still better than living an unfulfilled life haunted by regrets.

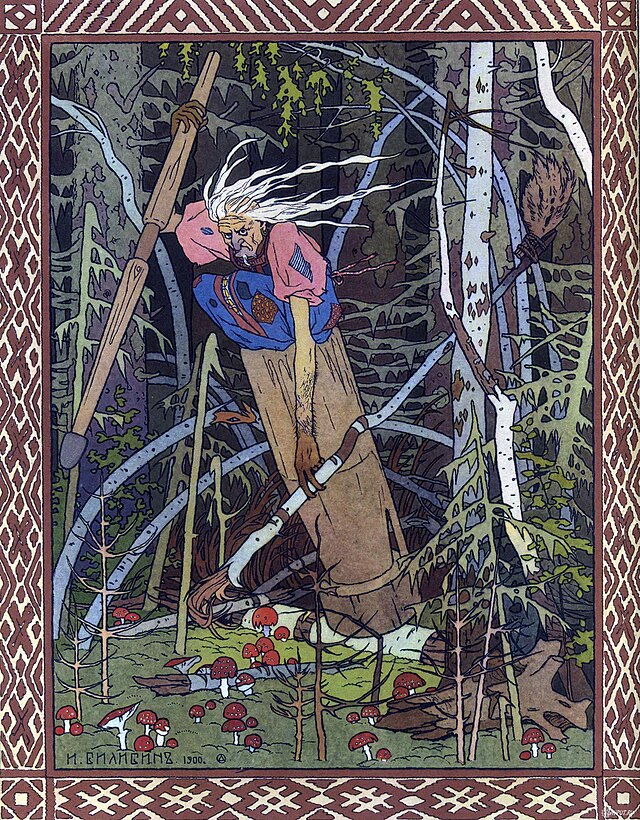

Crones are aiming to embody the archetype of Baba Yaga, a Slavic mythical hag with a healthy sense of dark humour, unapologetically authentic, wielding magical powers. She lives in a hut with chicken legs in the forest travelling in her flying mortar wherever she has business to do (goals?!). However, Baba Yaga is not a certain subculture of old women, going to farmer’s market, dyeing their own clothes with herbs but a part of us we should all embrace. We should all let our inner old women grow, so to say.

Baba Yaga. Source: Wikipedia

A Happy Ending

In 1950, American psychoanalyst Erik Erikson introduced his widely known theory of the eight stages of psychosocial development, each marked by conflicts to be resolved through relationships, connections, independence and so on. While the theory now seems overly simplistic and binary, and these stages can appear at any age, it underscores that we have choices about where to focus our energies later in life. From our 40s onward, according to Erikson, we should start to invest more in the well-being of others, create meaning, and contribute to society (starting earlier wouldn’t hurt, but it’s never too late). This approach can help us reach our 70s with a sense of wholeness, acceptance, and peace.

There’s no need for labels and archetypes to live up to, or even to put up an active fight for being visible again on society’s terms.

“Community is the antidote to invisibility”, according to Barusch. As I’m sitting in our garden in Amsterdam with my neighbours (all of them over 70), waiting for the pizza to arrive, casually snapping photos of each other (their phones are newer than mine!), I’m struck by how much difference financial stability makes in having a peaceful old age. But it’s not only money my neighbours have. They are surrounded by friends, active in WhatsApp groups with constant invitations to garden parties like this.

To see how much community matters, I have another example. My grandma wakes up at 5 am every morning to read the papers and discuss them with her neighbour and best friend at 6 am. But community isn’t the only thing she has. She is even more fulfilled than my Dutch neighbours. Her closeness to nature, the strong sense of purpose and constant engagement in manual labour. I almost never hear her talking about the past because she’s always busy with the present (what to harvest) and the future (will it finally rain in September?). There are always bees to be kept, honey to be made, wine to be sold and herbs to be dried.

Written by Mária Gubán.

Mária is a cultural journalist and an aspiring researcher of far-right movements living in Amsterdam. She has a degree in Psychology and Anthropology, and started her career as a theatre critic. Alongside writing, she loves picking up furniture from the streets and getting lost in nature.

Illustrated by Safae Boudrar.

Safae Boudrar, an illustrator and cartoonist from Morocco, is currently in her fourth year of architecture school at UM6P. A proud alumna of the Women Cartooning Fellowship, she mostly tackles gender equality issues with her drawings, but it’s not all serious. She also loves to spread warm thoughts and emotions through her breezy illustrations.