In March 2021, after British 33-year-old woman Sarah Everard was kidnapped and murdered by an off-duty police officer on her way home from work in London, my social media blew up. Sharing their personal stories of street harassment, women from all over the world – including myself – all of a sudden asked themselves the same question:

How have we come to normalise the “text me when you get home”-s, the long list of safety measures we take, the amount of consideration we put into simply leaving the house by ourselves?

Shocked by the recognition that literally all women I know feel more or less the same way, and knowing that most of those committing these crimes are men, I was kind of curious to see how my guy friends will contribute to the public discussion on street safety that was taking place on my socials. Shocker: they didn’t really (before you take it personally, exceptions do exist).

Then I watched the #notallmen hashtag surge and shift the focus of the conversation further and further from the core of the issue: what and who makes women feel unsafe, and why is it them to do the extra work of being “always careful”?

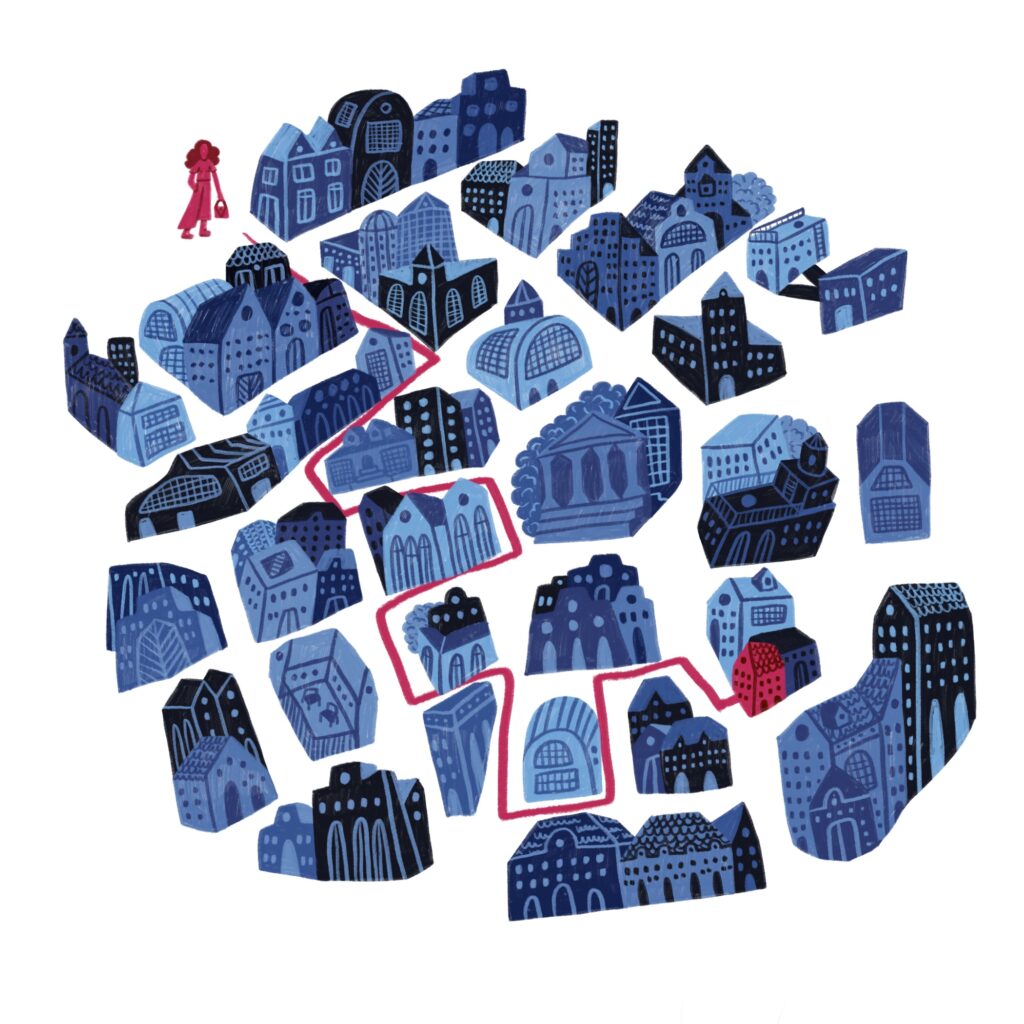

My initial anger and frustration had transformed into a sort of resentful acceptance of the fact that it will be us, women and marginalised voices, who will have to do the digging, the research and the convincing of policy-makers to take women’s perspective into account when designing urban spaces.

As I’m no expert on the topic, I’ve turned to researcher and activist Mirjam Sagi, whose work, among other topics, focuses on the security of marginalised groups in urban public spaces. Apart from giving multiple insights into the possible interlinks of gender and urban policy, her answers also made me reconsider some of my preconceptions when it comes to justice in public spaces: for example, it hadn’t crossed my mind that too much street security can also be counterproductive and was convinced by Mirjam’s argument for the need to avoid the over-policing of women’s bodies.

By @letdorabe

ZS: After Sarah Everard’s devastating murder, our collective awareness has been directed towards the fact that public spaces are still not a safe environment for women. But what about other groups and their intersections?

M: Your question is extremely important, – especially when it comes to policy-making – when people imagine victims of violence and especially violence against women, they tend to picture white, able-bodied, middle class local (i.e., non-migrant) women. At the same time studies have shown that homeless women experience sexual violence disproportionately in public space, and abuse experienced by Roma women, poor women or women in the sex industry tend to be dismissed and ignored. Because they are dehumanised and because they are often seen as non-sexual or overly sexual.

ZS: How can we make public spaces safer and more accessible for marginalised communities, through changes in urban policy?

M: It is tricky, because marginalised groups are generally not the target audience of such policies, due to the mentioned reasons and because traditional policing and securitization methods tend to criminalise marginalised groups disproportionately (e.g., racial profiling, criminalisation of homeless people) and tend to negatively affect the free movement/freedom of marginalised groups to a greater extent.

It is important to have actionable measures and it is expected from decision-makers, but the reality is that people want immediate tangible solutions to problems that can be solved meaningfully only in the long-run. People do not want to wait; they want to feel safe on their next night out and it is a reasonable desire, but one that is hard to meet if you don’t want to live in an overpoliced space.

Public spaces are essential components of democracy. If they become even more overregulated, we risk (completely) losing them as important spaces where different people, who wouldn’t meet otherwise, can pass by each other and potentially develop sensitivity through encounters. When walking in the city you can see the people, with whom you share your city.

Finally, urban governance should reflect on data and information at hand and should produce further evidence that is more sensitive towards the experience of women, minorities and marginalised groups.

It is a major issue in Hungary, for instance, that there have been so many changes in policies and crime data collection methods that now it is impossible to study public space-related crime statistics historically. One typical example I came across during my research is that from 2012 the number of CCTV cameras started to increase (due to a governmental tender for CCTV camera packages) and from the same year there is this huge drop in crime committed in public space in Budapest. Basically, this could even suggest that CCTV cameras are a great success, but we won’t know. Not only because we can’t isolate it from other determining factors (e.g., number of police officers, population change, etc.). But because there were two major changes in data collection. First, they increased the bar from which damage caused is considered a crime. Second, if a purse was stolen before, they registered as many crimes as many documents there were in the purse (2 bank cards, 1 driving licence and an ID = 4 registered crime), while from 2012 it meant only one crime.

These changes may as well be reasonable, but there is a good practice elsewhere to keep the previous data collection method parallel to the new one, so it is possible to study tendencies for better policy-making. These are however not city-level decisions, so it is also a question whether these issues should be addressed on the level of urban/local governance.

ZS: What should be given more attention when developing gender-sensitive urban policy?

M: I would highlight three points to be considered when developing policies. Two of them I just mentioned. First, to include the experiences of those who are considered “less deserving” in our societies and therefore their experience of violence is often overlooked.

Second, to reflect on the role of public space in creating/maintaining a more democratic, more solidarity-based society through passing by people we share our cities with.

The third is to be conscious of the difference between safety and fear. A false sense of security is harmful, but motivating fear is just as toxic. It is so easy to create fear in people and it can be exploited for political use extremely easily.

Reinforcing discourses around women’s lack of security in public space can lead to the over-policing of the female body and women’s free movement in public space – and it has been a long struggle for women to become more visible and accepted in public spaces.

It’s not far enough in history when prostitutes were called “public women” referring to the absurdity of female bodies in public space. On the other hand, such discourses easily become tools of scapegoating. People are more likely to believe that violence comes from strangers, foreigners, “Others”, when in fact women suffer from domestic violence – from someone they know – much more often.

ZS: What are some of the concrete urban planning tools that can counter violence against women – on the streets and on public transport? What is already available, and what can be a future solution?

M: It very much depends on the urban and socio-economic context. But in the short term, perhaps to have a police force that is sensitive towards the experience of (violence against) women and marginalised groups. There are some relevant training courses, but these should be a lot more than just ticking the box. Similar courses should be attended by those working in public transportation.

There should be greater cooperation between organisations that are able to develop and provide such training and the public sector (for sure in the case of Hungary). In the long term, the focus should be on the education of children, young people, and citizens in general – cliché, but true – to become more empathetic, sensitive and kinder can be learned and it must be taught. Industries with representational power also play a major role in such learnings (advertising, movies, pop culture).

And it is also crucial to understand the structural rootedness of power relations that lead to such violence (and fear) – Leslie Kern has a great book that is very relevant and just came out last year.

ZS: To what extent the sustainability, affordability and safety of cities overlap? Should we look for more holistic solutions, or rather tackle these matters separately?

M: They definitely overlap! It is worth looking for more holistic approaches, to look for solutions that are sensitive towards urban sustainability, wellbeing, and safety. Eventually, none exists without the other. In poorer cities, green solutions are further down on the priority list.

Poverty, but inequality in particular, leads to more crime creating more poverty and inequality; and those with more wealth will be more inclined in finding private solutions to their wellbeing, security, and health – and so on.

Finding more holistic solutions however is more complicated in practice considering the structure of decision-making. In most countries, I believe, separate ministries deal with each of these problems, but countries with larger civil service (such as the one in the UK) can afford to combine these matters more thoroughly. But even Budapest and even on a district level there are at least a few-yearly publications that are more holistic. How they are realized in actual policy making is another question.

ZS: Can you name a few real-life examples where positive change has already been achieved?

M: I think Vienna is a great example, especially in the Central and Eastern European context, but also globally, it has won the most liveable city in the world in so many surveys so many times. And one of the main reasons for this is the crime rate. While major cities like London or New York are hard to compete with in terms of “fun” (food, culture, gigs, etc), the safety, tidiness, and relative equality in Vienna puts it before the world’s major capitals. There are urban planning ideas that can achieve more friendly-looking spaces (e.g., with more green areas).

However, I don’t believe that crime or fear can be designed out of cities or spaces. I think crime and fear are less of a design concern than a social policy concern. An architect or an urban planner might disagree and come up with great ideas though.

ZS: Can the Austrian capital be a model for other cities, too? What are some of the “good practices” that the City of Vienna has achieved?

M: Yes, Vienna sets a great example on many levels – and actually, Vienna puts great emphasis on a more social approach to security. Instead of a penal one. It has a great social safety net, relatively cheap housing, more and better-quality public/social housing than in most of the European cities and these facts will affect the crime rate and sense of security (both from crime and in terms of social security). So, there are great examples in Vienna of how to achieve a society with less crime. We can even say a more “sustainable society”, but these are long term investments and won’t fit with election cycles. I am not sure about too many next-day solutions and recommendations, which is also because I am a social scientist, who believes in structural changes.

But there is a general consensus on having better lighting (which doesn’t necessarily mean more lights, rather more strategic use of lighting), wider pavements (to be able to keep distance), comfortable cycle lanes (for easier and safer moving around), more transparency, for example with shorter fences or no fences at all (but these will be private decisions in most cases). I think renaming public spaces with women’s names is a great idea that is visible and cheap. I would definitely recommend it. It won’t solve gender inequality or prevent crime though.

ZS: To what extent does the “one-size-fits-all” approach dominate the field of urban planning in Europe today? Is there a kind of “general” policy that every big city should follow, or should we be thinking of more “local” approaches to tackle these issues?

M: “One size fits all” definitely doesn’t work, but cities and urban planners can and should learn from each other. The involvement of local communities started to become a thing. Community planning, community-based urban planning or Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) is part of the EU agenda and it is great, but just like “gender mainstreaming” they often remain buzzwords to win funding and tenders. Even when there is a willingness to actually apply such methods it is often oversimplified. So I suppose there is some intention, but there must be more effort made.

Mirjam Sagi is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic and Regional Studies of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Her academic background and interest lie at the intersections of human geography, social theory, urban studies, and gender studies/feminism. She is a researcher and activist at the HerStory Collective.

Interview by Zsofi Borsi. Check out her latest pieces by clicking here!