Shock and Discomfort, Love and Empathy

It’s in 1983. I’m in Vienna on my gap year. Back in my place of birth and ready to grab hold of all that café culture, music, history, and most importantly, art.

That’s what I’m here for: to learn German and study art.

I head straight for The Albertina, a Habsburg Palace housing some of the most important collections of drawings and prints from the old Masters to early 20th-century art.

I’m here to see the drawings of Egon Schiele. I want to see them in the flesh. I rush through the sumptuously decorated State Rooms, wall coverings, chandeliers, fireplaces, marquetry, furniture. Ja, Wunderbar, but I’m here for Herr Schiele.

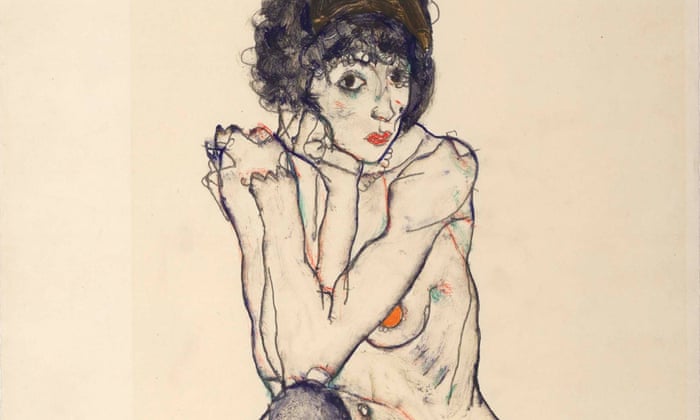

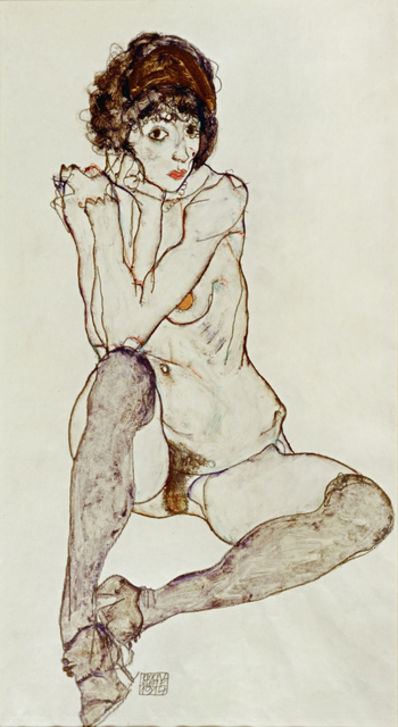

At last, I turn the corner and there she is. The Seated Nude (1914), my first encounter with The Man and his genius draftsmanship.

She stares at me with her legs open, her naked body stretches column-like up the centre of the canvas, ashen and ghostly but for the shocks of red on her lips, nipples and vulva. I’m uncomfortable. Is it the red bits? Is it the celebration of pubic hair? Or is that she stares so directly, her dark eyes wells of knowing? She’s seen it all and been there. No time for artifice, just life laid bare; angst, flesh, flesh and yes, that crotch staring at me; yes it’s been there, seen it all. I wanted to stare and at the same time look away. I loved the anxious lines, the embrace of flesh and bone, the attitude.

At the age of 19, I wanted to be bony and bolshy and I wasn’t. I wanted to experience life on a knife-edge and I hadn’t. This was the Vienna of the grotesque, the erotic, the world studied by the innovators and intellectuals of Fin de Siecle such as Freud, Schonberg, Oska Kokoschka and Schnitzler. A melting pot of ideas. What happened to that melting pot? Where was that pot now? Well, all that ended with the arrival of a certain Herr Hitler. Shh, we don’t talk about AH, the Viennese don’t like it. But wasn’t he Austrian? Shh!!

It’s in 2019. The Royal Academy in London is holding a major exhibition of Klimt and Schiele drawings. I’m there. And there she is, all flesh and bones, looking at me with those dark eyes and that red crotch. But this time I look straight back at her and yes, at the crotch. No turning away, no awkwardness. Her gaze is no longer bolshy but resigned, fatalistic. I linger and really observe those crisp lines that artfully capture her casual sensuousness. I feel awe and love. Awe at Schiele’s genius and love of his subject, a sort of motherly love. Empathy.

Since I saw her last I had learned how to be bolshy, it got me nowhere. I’ve been there (well somewhere) and done it; well, married, divorced, married again and brought up two fantastic sons (I got lucky there) and I got the bones (overrated and not worth it). This dear girl is 14 going on 40. Most probably a prostitute, his subjects often were. He was financially strapped and they were cheap and used to taking their clothes off.

So now I’m asking myself, was he a sex offender? Was this exploitation wrapped in art? His nudes were often criticised at the time for being pornographic. Yet, they sold well. “The more pornographic, the easier to sell,” remarked his contemporary, Oskar Kokoschka. Were these women there of their own free will? Did they have any choice? Did he care? Or did he draw them in such a way as to render them genuine sexual agency? He apparently had a great admiration and love for women, but also boasted that he had had 180 women pass through his studio in just 8 months! “Had”, or received? And we cannot forget that many of his subjects were children, minors, with no voices, let alone rights.

And what are we, the onlookers, voyeurs? Are we complicit? Do we need reminding of the circumstances when we do look, do we just ban them outright? Schiele still causes controversy and makes us feel uncomfortable in his art; his pieces are disturbing, but doesn’t all great art force us to question? And what’s wrong with feeling uncomfortable? The enduring relevance of great art lies in such questions, in ambiguity rather than simplistic formulations.

I’m going to take a step back and come off the fence. I’m more enriched by the existence of his work – his drawings bring me more pleasure every time I see them. I wasn’t offended as a 19-year-old, and I’m not now. It’s a different time, and thankfully we are in the age of #metoo. We are all quite capable of making up our own minds. To me, Schiele was, without doubt, a great artist and died far too young, aged 28 of Spanish flu, (no COVID comparisons here). I can only imagine what he might have gone on to achieve before “you know who” arrived in town. Schiele elevated drawing to a new independent status. A master in draftsmanship, placing the human body at the centre of his concerns.

Written by Erica Cosburn.

Erica was born in Vienna and grew up in London. Having studied at Chelsea School of Art, she worked as an interior designer for 20 years. After bringing up two sons and launching them into the world she joined Smartworks, a charity helping low-income and single mothers get back to work, dressing them for interviews and providing interview training. Until recently, Erica had rarely written anything apart from shopping lists and a sketchy diary. But lockdown has provided the opportunity and headspace for her to write, as well as relearn the piano and drawing.