A ring in the shape of a crown and a simple silver ring adorn Julie’s ring fingers. She received one from her father, the other – a religious symbol – from her mother, she says, as she shows them to the rest of the group, gathered on Zoom to discuss some of the topics brought up during Julie’s conversation on the ‘Making It’ in Western Europe podcast.

The rings are her answer to what precious object she took with her when she left Russia after being arrested for protesting the country’s invasion of Ukraine.

The aim of PodTalks—a series of conversations following the release of each episode—is to bring together those who want to delve deeper into some of the topics raised in the podcast. It is a chance for the community to comment, share their own experiences, and ask follow-up questions.

Detention in Moscow

The conversation starts with everyone sharing what sentimental object they couldn’t leave home without, from jewellery to books, to childhood photographs. But it quickly moves on to the heavier topic of Julie’s arrest.

“What happened exactly in Moscow?” Frosso asks. “I think we’re all familiar with Russia’s repression tactics, from what we read in the press. But the perception we have really does change when we have people we know who have gone through the situation. So what does it mean to be detained in a detention centre because you were participating in a protest?”

Julie remembers vividly the weekend that it happened. She was out getting her nails done and was pleasantly surprised to find out that the location for the protest was close to the nail salon. With her nails freshly done, she walked out and went to gather with her friends, where they wanted to take some photos.

“When we came to the place of the anti-war protest, I noticed that there was a lot of police and a lot of press. And usually, if you’re an activist in Russia and you see so many people in one place, it’s never a good thing,” she laughs. “You know that you’re outnumbered.”

The arrest happened very fast. Julie says she couldn’t even think and just accepted the fact that she wasn’t going back home that night. There were about 20 people stuffed into a prison truck, one of many parked near the place of the protest.

Quick thinking prompted her to text human rights organisations and her colleagues to tell them to remove her from any conversations that could create problems if the police gained access to her phone.

“We understood that no one is going to let us out any time soon. They were driving us to the police station,” she recalls.

She spent two days in the police station, which she feels was the toughest part of her detention. Although her friends brought things like water, food, and hygienic products, the police kept them waiting and tried to scare them.

“After that when we went to the detention centre it was better, it was like a feminist paradise…because all the political girls are together in prison. Before that, there was emotional abuse. I can’t even remember distinctly, because some part of my brain must have erased the memories,” Julie says.

This is not an unusual occurrence in Russia these days. Julie and her friends knew that every time they went out to protest, they were doing something illegal. They would pack their bags with a change of clothes, toothbrush and whatever else they might need in case they got arrested. Sometimes you can get away with just a fine, but sometimes you’re also detained for several days.

In Julie’s case, she was detained for 10 days. Another girl, who was arrested for the second time, was detained for 30 days.

Although Julie is now in France and doesn’t think she will go back to Russia any time soon, she wants to continue her fight. From France, she believes she can do more to help people inside the country rather than from prison.

But she admits everything is not perfect in Western Europe, either.

“I realised that I should keep in mind that countries are really different, even in a ‘unified’ Europe,” she says. “There are so many nuances and particularities one should pay attention to.”

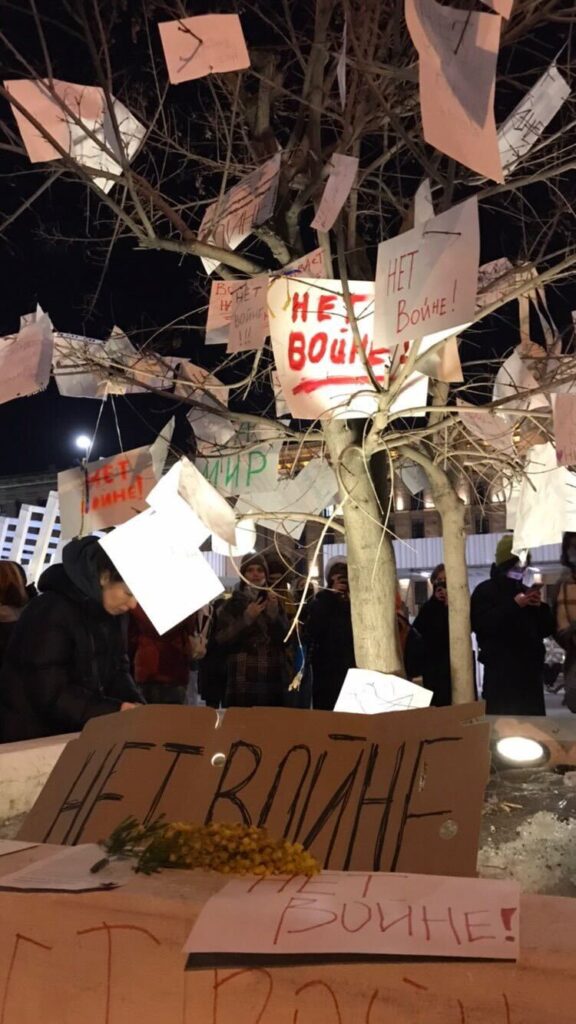

Julie’s pictures from protests in Moscow.

The “French girl” standard

The difficulties of the French language and being accepted by people in France when not speaking the language have always been discussed among expats. It is an image that France is trying to change. Although Julie and others in the discussion still highlighted the challenges of being accepted in France.

One of the biggest challenges is the “French girl” stereotype and the country’s “natural” beauty standards. It’s funny that the only person who hasn’t heard of this stereotype is the only French person in the group, Eloise.

Delving deeper into points raised by Julie during the podcast, there was talk of how the way everyone thinks about make-up has changed since their school days, with Dorina highlighting that it is not specific to France.

“I encountered this in Hungary as well. If the woman doesn’t look good after waking up, if you need to put the effort in, you’re not pretty. But if you put too much effort in, it’s also not pretty,” she says. “Since I’m in Austria, I’m okay to go out without make-up…I’m much less concerned in Austria with my look than I was in Hungary.”

Frosso adds: “I think there is a value in questioning the value of make-up and considering how much time it takes us, how many decisions we need to make on a daily basis with regards to our beauty, compared to everyday decisions that my boyfriend has to make. He doesn’t spend an hour deciding what moisturizer to buy. There is no way to win in this unless we start questioning these standards as a whole.”

But beyond these challenges there is a lingering question for any immigrant. Do you work to be a so-called “good immigrant,” and how do you feel about critiquing the state of the country you’re currently living in?

And for this, Julie has a good response.

“I don’t feel like I’m obliged to worship the country that accepted me. I’m really thankful but I feel like there is always room and space for critique.”

Giving immigrants who are smart, young, and ambitious a chance to better their host country and suggest improvements can only be good.

Listen to the full podcast episode with Julie here.

Written by Selin Bucak. Find her latest articles here!