It was November 2019. The first month of my PhD in Florence, and as a wide-eyed newbie, I wanted to experience everything the city had to offer. In my research, I focus on the intersection of art and politics, so you can imagine my excitement when I came across a flyer advertising a festival of art documentary films. I immediately bought a pass and circled out pretty much everything – biopics of eccentric (un)known artists, snippets of raves and protests, and films dealing with questions of gender and sexuality. I mean, what was not there to like?

A few rainy days later, I was sitting in the cinema hall, ready to absorb yet another dose of creative inspiration (because who cares about work responsibilities when a festival is in town). That evening’s feature film, Beyond the Visible, portrayed the life of Hilma af Klint – a Swedish painter and possibly the true pioneer of abstract art, except that this primacy was taken away from her.

What History Books Don’t Talk About

If we look into mainstream art history books, we learn that the first painter to adopt abstract art as his primary medium was Wassily Kandinsky. The issue is that someone else had made this shift almost a decade before him but her name is still mostly absent from university curricula. That would make sense if her works were produced completely privately, never to see the light of day. But that wasn’t really the case, at least not quite. Hilma af Klint was a recognised artist with a degree from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, one of the few places where women were allowed to study at a university level. Her early, mostly figurative works were regularly exhibited, and unlike many of her female counterparts, she managed to actually make a living off her art.

In 1896, Hilma, together with four other female artists, founded The Five: an esoteric spiritual group organising weekly séances. For many, theosophy presented a women’s liberation philosophy, as it raised them to the role of priestesses: something normally available only to men. During these sessions, the artists prayed, meditated, and recorded messages believed to be coming from the afterlife, which they captured through experimental automatic writing and drawing. These formed the basis for Hilma’s abstract artworks later on, an attempt to design “a new philosophy of life,” just like the High Masters requested from her.

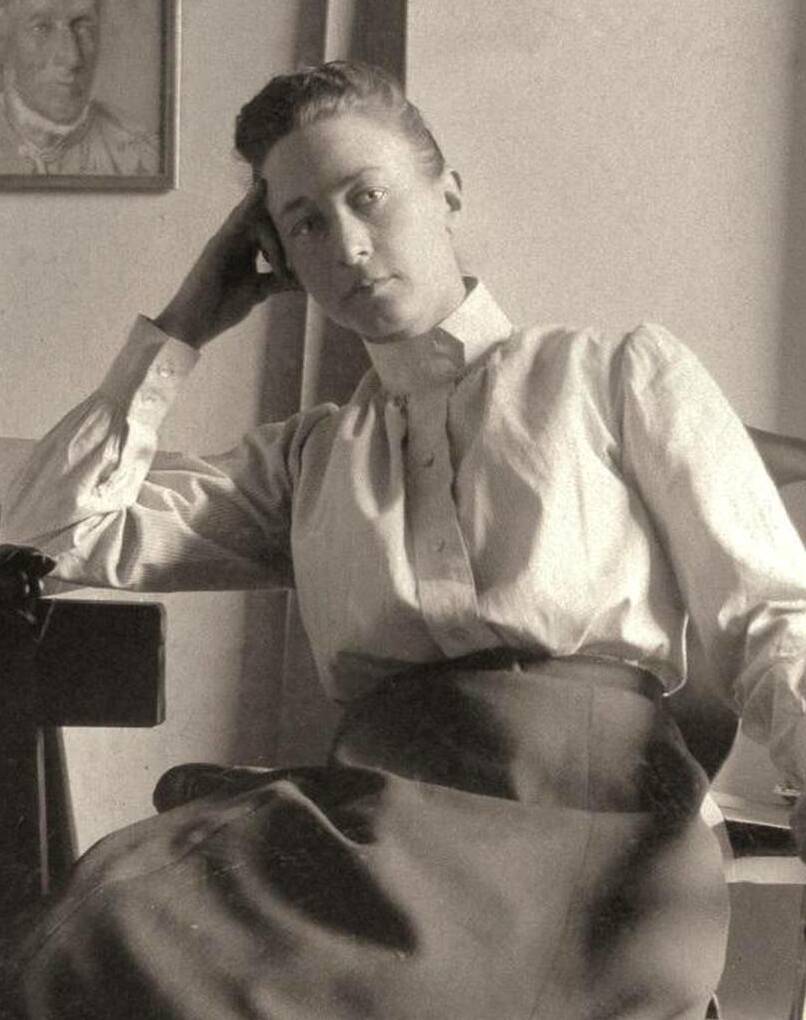

Hilma af Klint. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Between November 1906 and March 1907, she painted a series of small-format abstract canvases, followed by The Ten Largest: a series of monumental, 10 feet tall canvases filled with intertwined spirals, circles, and serpentine lines, painted in radiating bright and pastel colours, exploring new realities usually inaccessible to the five senses. However, following the advice of Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian occultist and founder of Anthroposophy that Hilma looked up to, she kept this work secret, made to believe that the public was not ready to see such radical works. Before she died in 1944, still worried her work would not be properly understood, she requested it to remain hidden for at least 20 years after her death. In the end, she left behind some 1200 paintings, 100 texts, and 26 thousand pages of notes, buried from public sight until 1986, when they were first exhibited in Los Angeles.

Stolen Spotlight

Staring at her large-scale, almost metaphysical canvases on the cinema screen, I suddenly started crying. I could not really explain why – maybe the artworks spoke to me in some way, maybe it was the painful injustice surrounding her career that enraged me or the violence of simply erasing this wonderful woman from history.

Her work was like nothing I had seen before – colourful and playful but with such a deep message hidden within that it made me gasp.

I needed to see it in real life, curious what impact it would have on me.

It was not until my visit to London this summer that my dream finally came true. The Forms of Life exhibition at Tate Modern promised “a unique chance to discover the visionary work of Swedish painter Hilma af Klint and experience Dutch painter Piet Mondrian’s influential art in a new light.” And that it did. I could not help the feeling that the exhibition was mostly about Mondrian, yet another man to steal Hilma’s spotlight. From their strategic position as the first artworks to be seen while entering the common rooms to Mondrian-themed donuts in the gallery cafeteria, it quickly became clear that af Klint’s work was just a supplementary tag-along, an interesting rarity to accompany “one of the history’s most influential” men. Even the curatorial logic dividing the artists’ works into different thematic blocks seemed to be informed primarily by Mondrian’s work, with af Klint’s “unfitting” or “uncategorizable” notes and illustrations lumped together in one chaotic room in the middle of the exhibition.

We had to wait until the end before we finally got some “alone time” with Hilma’s pieces.

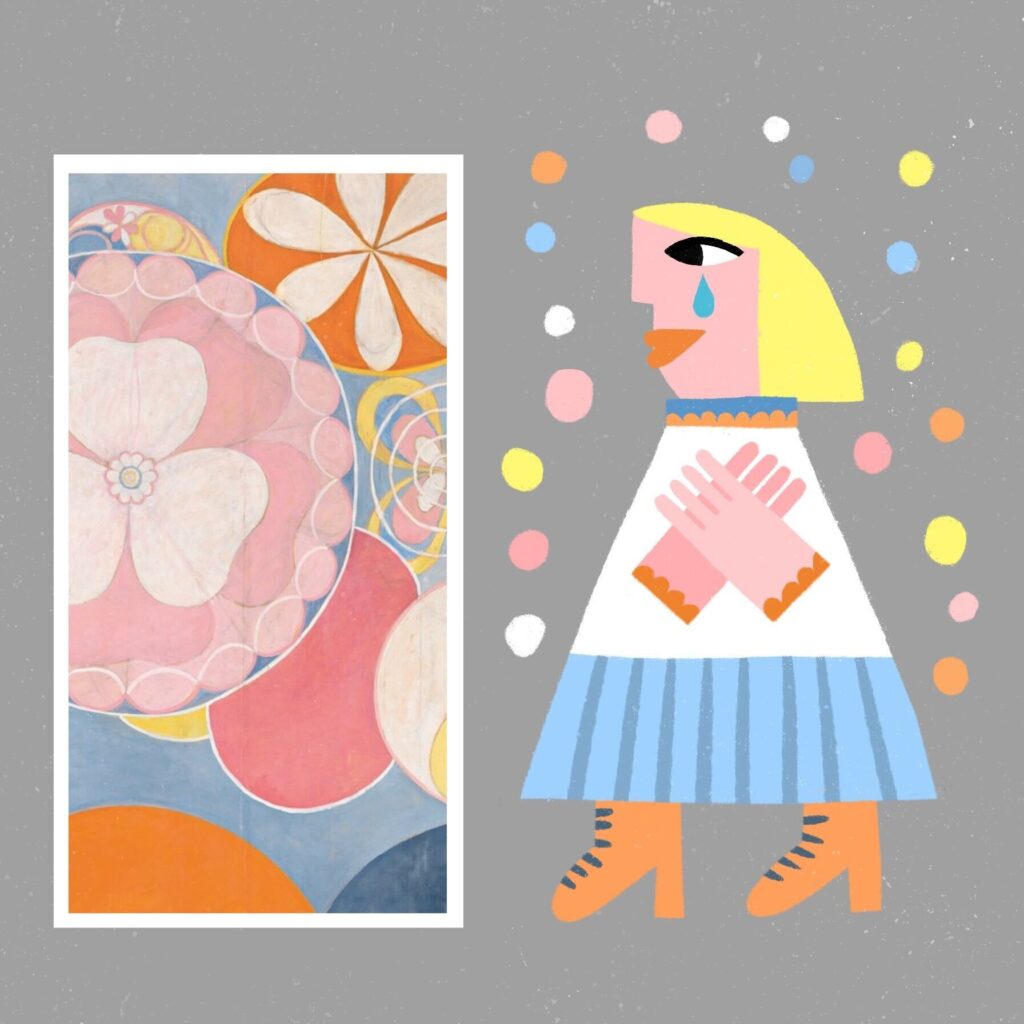

Artwork created for Lazy Women by Benedetta Bellemo.

A quiet understanding

Sitting down to admire her process of abstracted deconstruction with elements always intertwined in perfect harmony, or timidly walking around her large canvases in the dimly lit room, I felt a sudden wave of warmth and calm.

Some form of quiet understanding, as if the paintings were trying to tell me something that, deep down, I already knew. In the movie, some visitors started crying uncontrollably when encountered with her work, as if something that was hidden, that they could not quite name, was finally made visible. The gallery was too busy for such an intimate experience but was powerful nonetheless.

Despite all this, how come it took so long for Hilma af Klint’s work to achieve the global acclaim it definitely deserves?

How come that even nowadays the first names that come to mind when we speak about abstract art are those of Kandinsky and Mondrian? “It’s easier to make a woman into a crazy witch than change art history to accommodate her. We still see a woman who is spiritual as a witch, while we celebrate spiritual male artists as geniuses,” argues Halina Dyrschka, the filmmaker behind af Klint’s biopic. And I tend to agree.

Af Klint’s theosophical spiritual practice, although met with suspicion by some locals, was extremely common in artistic and intellectual circles at that time, with Kandinsky or Mondrian being no exception. However, the avant-garde movement, as many before (or even after) it, was heavily male-dominated, making it hard to break into.

Compared to her counterparts, Hilma’s artworks are also openly “girlish”.

Pastel pinks, purples, light blues, oranges, and soft yellows, together with depictions of the female womb and gender divides, lie in stark contrast to the strict lines and bright, almost aggressive colour palette of the other two.

This probably made it much easier to cast her out as an infantile “wannabe mystic” and a “crazy witch.” But just like she believed her whole life, her time was to come eventually. Since her “re-discovery,” af Klint’s work has become an international sensation, even becoming the most successful exhibition in the history of the Guggenheim Museum in New York with more than 600 thousand visitors. A decent outcome for someone who did not “officially exist” just a few years before that.

In 1971, an essay titled “Why have there been no great women artists?” was published by art critic Linda Nochlin. I think this question is quite symptomatic of our times, filled with “new discoveries” of trailblazing female painters, literary figures, scientists, musicians, or even ancient female hunting queens on a nearly annual basis. It is not that these women did not exist, we just chose not to see them. But they are slowly becoming harder to ignore.

Written by Lucie Hunter.

Lucie is a PhD candidate in Political Sociology at Scuola Normale Superiore in Florence, Italy. While not at university, she is managing Lazy Women or works as a freelance (documentary) filmmaker and podcast editor. You can usually find her roaming through Florentine galleries, passionately/obsessively advocating for the societal role of art, or sipping red wine in a local enoteca.

Illustrated by Benedetta Bellemo.

Benedetta Bellemo is a Paris-based illustrator. Originally from Italy, she worked across Europe in the field of Sustainable Energy before moving, in 2021, to full-time illustration – her true love. Her universe is made up of strong women and quirky animals strolling between humor and metaphysical questioning. She works in editorial illustration, children’s books, walls, and all the surfaces in the world on which one can draw.