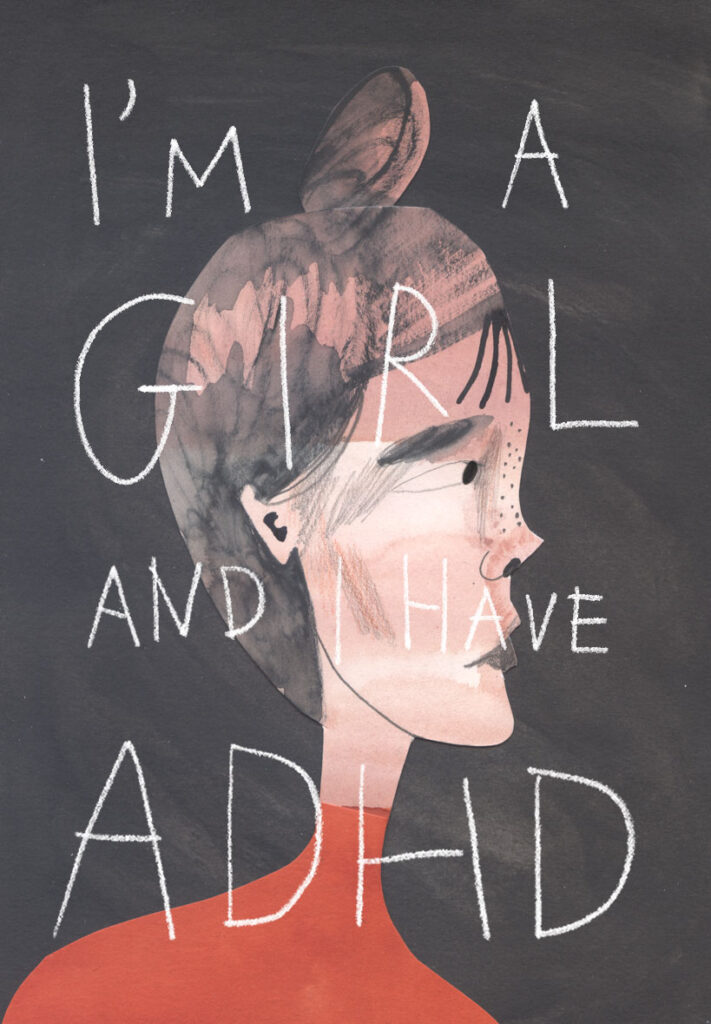

It’s quite hard to navigate my identity as a woman with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

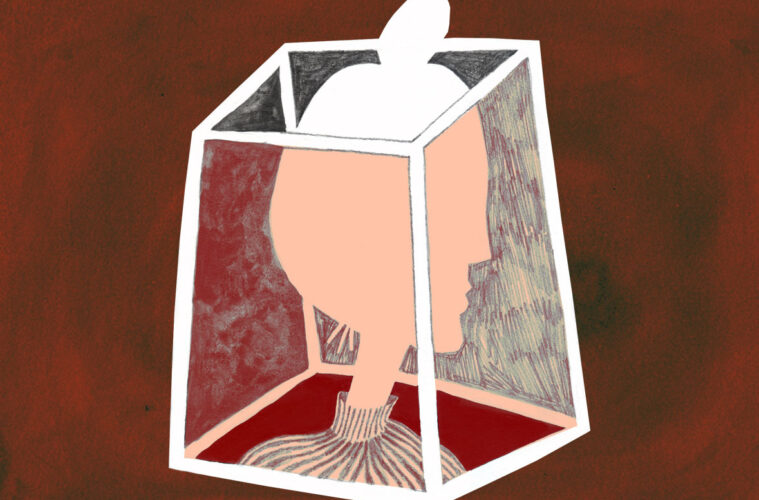

Disorganised, clumsy, impulsive and definitely a danger in the kitchen – I’m criticised for being so unlady-like. On the other hand, people question my diagnosis as I don’t act like a hyperactive boy. I’m trapped in a wrestling match with gender stereotypes. For many women with ADHD, societal preconceptions of gender have played a key role in hindering their access to diagnosis, support and empowerment.

It took 23 years for me to be diagnosed and medicated for my ADHD. Although I was diagnosed with dyslexia in Year 2, my ADHD was never picked up on during school, or in my undergraduate and postgraduate studies at university. This isn’t an uncommon story, as it’s estimated that 50-75% of women with ADHD go undiagnosed.

“I’m trapped in a wrestling match with gender stereotypes”

I’m sure your first thoughts of ADHD invoke the image of a young boy bouncing around a classroom, rather than a daydreaming girl sitting at the back. However, ADHD can present as three types: hyperactive, inattentive and combined; males typically express the hyperactive kind, while females are more inattentive. Although neither ADHD type is more severe than another, hyperactive symptoms are commonly overt in expression. As a result, the restless, impulsive, fidgeting boy often dominates our understanding of what ADHD looks like.

My mood-swings, impatient nature and questionable spending habits have never fit this stereotypical image of ADHD. Instead, my symptoms were often explained as character traits – “lazy”, “disorganised”, “clumsy” – to name a few.

This is often the case for many women, as traditionally the condition was thought to affect mostly males, and it was only relatively recently that women have begun to be diagnosed and treated for ADHD. As research has developed, so has the recognition that sex plays a big role in how ADHD affects men and women. However, according to the ADHD Institute, ‘despite the apparent gender differences, research has mainly focused on ADHD in males; the pool of research into ADHD in females is slowly increasing, yet is still limited’.

With the limited research available, there are some significant findings. While ADHD symptoms often develop at a young age in boys, symptoms in girls typically appear at the onset of puberty. Anne Arnett, a clinical child psychologist, discovered from an extensive study that sex differences could explain why boys tend to express more extreme symptoms, and a broader distribution of symptoms, than girls. While male symptom’s severity usually stays at a constant level, the female hormonal cycle often dictates the severity of a female’s ADHD, as hormonal fluctuations prior to a woman’s period can result in the worsening of symptoms.

Girls often differ from boys in the coping mechanisms they use. While girls with ADHD sometimes struggle with keeping up with friendships, girls often try harder than their male counterparts to compensate for their ADHD symptoms and are more willing to put in extra work to try and fit in. Unlike teenage boys who tend to act out, girls will typically internalize their struggles. Most concerning, this internalisation can be a major contributor to why women with ADHD are more likely to experience major depression, anxiety and eating disorders than girls without. New research suggests that to effectively diagnose and treat ADHD symptoms in women, doctors should consider ‘hormonal fluctuations, trauma, family dynamics, self-esteem, and eating habits’. If you want to learn more about gender differences in mental health, check out our recent article discussing mental health for all.

While these studies highlight the significant role sex plays in different presentations of ADHD symptoms, hyperactive white boys still shape the diagnostic criteria used today. According to Vice, the coverage of ADHD in the US media often portrays that children are being over-diagnosed and over-medicated, yet it is estimated that four million girls and women are going undiagnosed and untreated. King’s College London states that depending on the research you look at, the ratio of boys to girls with ADHD diagnosis ‘could be anywhere between 2:1 and 10:1’.

“Many women and girls still face criticism and misunderstanding around their ADHD”

To learn more about women’s experience with diagnosis, I spoke to Amber, a 22-year-old primary school teacher. With her brother diagnosed at twelve years old, Amber never considered that she could also have ADHD, as her symptoms were very different from her brother’s. While struggling at university, Amber started doing research online, and was amazed that she found all of her symptoms were connected to ADHD. Since her diagnosis, her close family and friends were not surprised, yet for everyone else she meets – in her words – ‘they are incredibly doubtful [of my diagnosis] and I find myself constantly justifying my diagnosis which is really frustrating.’

Misdiagnosis is very common for women and girls, as they are more likely to be diagnosed with an emotionally based psychiatric illness, such as depression or anxiety, before being diagnosed with ADHD.

According to the American Psychological Association, the lack of support and treatment for women with ADHD is extremely concerning, as these females are two to three times more likely to attempt suicide or injure themselves as young adults than girls who do not have ADHD. Undiagnosed ADHD can cause life-damaging consequences, as a delay or lack of support can result in other conditions such as drug and alcohol addiction, bipolar disorder, OCD and PTSD.

Beyond the struggle for proper diagnosis, many women and girls still face criticism and misunderstanding around their ADHD. Even today, with my diagnosis, I am still told that my ADHD isn’t really ADHD, it’s just me. My forgetfulness isn’t a symptom of a chronic condition, but rather my lack of self-will to try harder to remember.

Speaking to Lazy Women, Sophia, a 22-year-old masters student, described facing similar struggles. Diagnosed at five years old, Sophia has faced mixed reactions to her diagnosis, with some people asking questions like, “I thought if you had ADHD you would be jumping up and down all the time?” Sophia believes that there are many misconceptions about ADHD, and that people do not understand its effects. Even after ten years of medication, she has experienced people, even family members, have been doubtful that she still needs to take it, and in her words that she “just need[s] to try harder”. With her ADHD symptoms sometimes being passed off as character traits, such as being lazy or forgetful, Sophia has struggled with feelings of self-loathing and guilt when trying to accomplish simple tasks. Looking towards the future, Sophia is worried about being an adult with ADHD, as she believes people often assume that you just “grow out of it”, and that as she gets older, the tolerance around her ADHD will deplete. She fears that people will assume her to be an irresponsible adult, rather than a woman struggling with ADHD, and she is especially concerned about saving money and the challenges that come along with motherhood.

For many women with ADHD, this is a relatable story, as their symptoms can often be a source of embarrassment, and as young girls grow into women, taking on roles as mothers, wives and caretakers can be especially difficult for women with ADHD.

These stereotypical female roles often dictate the need to be selfless, organised and mild-mannered, unlike their male counterparts, and for women with ADHD, they may struggle with being able to fulfil these responsibilities in a way that is acceptable to society.

According to ADDitude, as women with ADHD internalise criticism, they assume they are failures because they cannot keep up with the societal expectations often placed on women. These feelings of shame are a large part of the reason why so many women with ADHD ‘struggle with a mood disorder, anxiety, and low self-esteem, in addition to ADHD symptoms like inattention or impulsivity’.

With limited research available on women with ADHD, the male experience has often been promoted as the only experience of ADHD. For the women who do not fit within the male stereotype, they have instead had their condition passed off as flaws and criticisms, rather than receiving the support they so desperately need. Furthermore, while there are so many benefits to being a woman with ADHD, societal expectations of female roles and character have often stopped women with ADHD from feeling empowered and confident in their abilities.

Although my support and medication have helped me to cope better with my ADHD, I will always be a clumsy, disorganised and impulsive woman. However, what can change is our societal response to ADHD, by moving away from using gendered stereotypes to dictate our definitions of success and failure for women.

Written by Jo Crawford.

Jo Crawford is a master’s graduate in Conflict, Security and Development from the University of Exeter. Starting out as an ambassador for the British Dyslexia Association, she has since been combining her passion for journalism with her interest in human rights. Jo has been conducting human rights research both in the field and online and is currently working as an investigative writer for a feminist think-tank.

Illustrated by Kata Kocsispéter.